Kim H. Esbensena and Claas Wagnerb

aKHE Consulting, www.kheconsult.com

bSampling Consultant—Specialist in Feed, Food and Fuel QA/QC. E-mail: [email protected]

This column has so far treated primary sampling from lots in all shapes, forms and nearly all sizes—but the lots treated have all been larger than the typical sample on the laboratory bench. The main lesson from the previous 11 columns was simple and powerful: all types of lots in this size range and all types of materials can be sampled based on the exact same principles, codified in the Theory of Sampling (TOS). Lot size, material, form… in a crucial sense do not matter, all that matters is the degree of heterogeneity that has to be counteracted by the sampling process. With one exception, however, lots that move… dynamic lots. The arena of process sampling will be treated in full in just time, but here-and-now the focus shall be on completing the realm of stationary lot sampling, by closing the lot size range. With this and the next column we are finally moving into the laboratory focusing on smaller and smaller lots. It does not matter that occasionally some of these operations will take place in the field (think of a large primary sample conveniently being split down in the field with obvious transportation or other advantages). For systematic convenience we shall treat all stages and operations performing sample splitting etc. as taking place in the laboratory—without loss of generality.

Representative sampling—a scale invariant endeavour

Sampling of small lots of the size typical of the work taking place on the laboratory bench, sub-sampling, sample preparation, final aliquot extraction… all involve a greater-or-lesser part of sampling of the same kind as has taken place before the lot in question arrived in the laboratory (indeed sub-sampling is nothing but sampling). The unifying principles promulgated by TOS are all with one aim—to make sampling from heterogeneous materials as simple as possible with the imperative of being representative, at all scales. This is simply a continuation of applying the same TOS principles all the way from the primary lot to the final analytical aliquot. Thus, one of the most powerful unifying governing principles in TOS is that representative sampling is scale invariant. The physical dimensions of the sampling tools change so as to be commensurate with the lot size. However, the essential issue is that the sampling process at all times (and scales) is 100% focused on how to counteract heterogeneity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The laboratory—the realm of the spatula. At this ultimate stage of the long sampling pathway from the original lot, significant sampling errors can still crop up, mostly due to a faulty understanding that if the material appears homogenous this justifies grab sampling, spatula sampling. NOTHING could be further from the truth, however.

Another of TOS’ simplifying principles is that any reduced mass of the original lot (of course preferentially a representative sample thereof) can be viewed as a lot in its own right. This means that at any sampling stage one may temporarily view the current lot as a “primary lot” from which to extract a primary sample (if this is advantageous). This “local viewpoint” is obviously not a statement meant to disregard the full pathway, on the contrary. But this local focus leads directly to the understanding that one is faced with exactly the same challenges as when facing the original (larger) primary lot. The local lot is still heterogeneous with all the same ensuing issues… in fact it is only the size of the contemporary lot that is different, nothing else. The sampler is still facing the same fundamental problem as when facing the original lot size: how to extract a representative sample from a heterogeneous sample? The lot in question just happens to be smaller than its original precursor.

But since the problem is identical, so are the optional solutions: representative sampling is scale invariant. It is only the sampling tools that will have to change their physical dimensions—everything else remains identical. There may, or there may not, be a smaller heterogeneity in the lot now residing on the laboratory bench, depend on the preceding sampling process, i.e. whether some sort of splitting was invoked or to which degree mixing was part of a composite sampling procedure etc. This is actually not even an important issue—what is certain is that also all sub-samples of original heterogeneous lots are also themselves intrinsically heterogeneous. There can, therefore, be no slacking of the demands for representativity at any smaller scale than the size of the original lot (Figure 2).

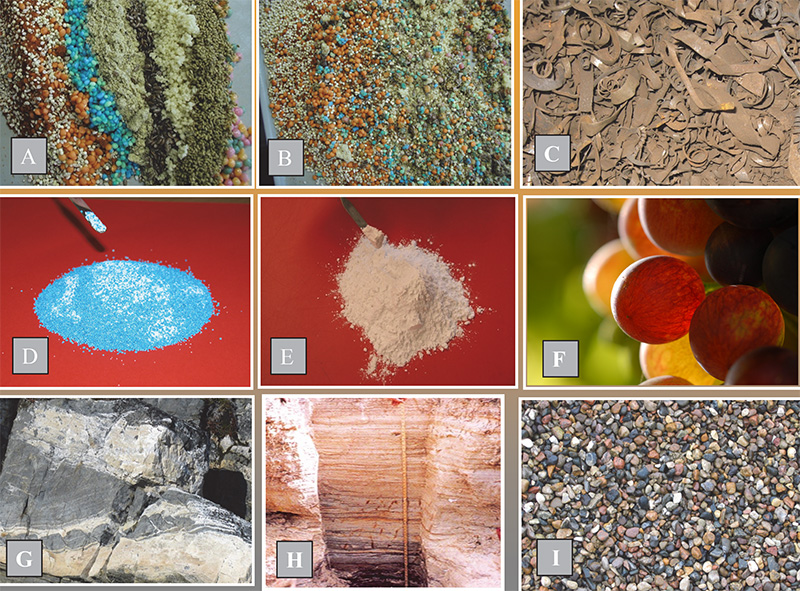

Figure 2. The phenomenon of heterogeneity is intrinsic to each lot material (always displaying both a compositional as well as a spatial component, CH and DH). For this understanding, which determines the necessary sampling process (composite sampling always—never grab sampling), it does not matter what came before. It is actually immaterial that of the “lots” depicted only panels F, G and H are primary lots—all other panels depict samples from a particular later stage in the generic “from-lot-to-aliquot” pathway.

These issues are emphasised with the aim to disallow any-and-all arguments that may be levelled in order to try to justify that different sampling demands reign at the significantly smaller laboratory scale or that different types of sampling equipment are needed, or acceptable, at this scale in the laboratory realm. Following the logic of TOS there can be no other demands to either procedures or equipment at the laboratory scale as at all higher scales. TOS’s six governing principles and the four Sampling Unit Operations recognised by TOS are the only tools available with which to address sampling—at all scales (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mesoscale grab sampling (left) vs micro-scale in the lab. (right)—what is the difference? This is the wrong question, at the wrong time and at the wrong place (scale)—what matters is that heterogeneity follows suit all the way to the final aliquot extraction. It truly does not matter whether the human eye can discern any material heterogeneity, or not—60+ years of experience allows TOS to state categorically that all materials are significantly heterogeneous and shall therefore be treated accordingly. This insight actually makes all of sampling immensely easy: act as if all lots, all materials, at all scales are always heterogeneous.

This understanding has many, perhaps at first silly manifestations and consequences, e.g. a digger, or a front loader, with a one-ton front grabber is identical to a spatula! Identical in the way it may be used wrongly to perform grab sampling if only one increment is extracted and wrongly pronounced as a “sample”. It is the faulty grab sampling procedure (one increment only) that is identical, albeit performed with radically different sized implements (one ton vs a few grams, perhaps). In this context a digger—is a front loader—is a spoon—is a spatula (Figure 4)!

Figure 4. Sampling tool size is set to match the lot size first, but the key function of any sampling tool is always to counteract the material heterogeneity present (CH, DH); see also Figure 3.

As with all inherent sampling characteristics (governing principles, unit operations, sampling equipment) the task of the competent sampler is to look behind the superficial manifestations—to find out whether apparent sampling usages actually comply with the simple (6 + 4) demands of TOS, or not. If not, it will never be possible to qualify a particular sampling process as representative, no matter how “ingenious”, “smart”, “labour-saving”, “practical”… at first sight.

Size does not matter—only heterogeneity, and how to counteract it

Figures 5–7 give a few illustrations, all from the laboratory realm. Enjoy how there is absolutely no difference here with respect to examples presented in earlier columns relating to larger scales. Once the simplicity of the governing principle: “representative sampling is scale-invariant” has been comprehended in full, a massive empowerment ensues. Size never matters again—only heterogeneity.

Figure 5. Even at laboratory scales, segregation may present serious heterogeneity problems. Composite sampling is imperative, with the critical proviso that all increments must cover (counteract) heterogeneity in the vertical direction (see previous SE Sampling column on “spear sampling”). The exact same principles apply in the laboratory as everywhere else.

Figure 6. Perhaps the world’s most misplaced sub-sampling call: in the process of crushing carefully collected 12 kg composite field samples (>16 increments, as illustrated), assisting students were told by the analytical laboratory head to “forget all this TOS stuff—the usual procedure here is to select a lump the size of what is needed for further treatment and only crush this mass instead of all the silly 12 kg” (the indicated lump is circled—20 g). Luckily the students involved were sufficiently competent w.r.t. TOS to have the courage to neglect such “advice”. There is a (sacred) reason why the field composite samples weighed in at a minimum of 12 kg—specifically to counteract the very troublesome field heterogeneity encountered. The suggestion to skip the crucial full laboratory crushing stage would have produced a ~600 times smaller sub-sample (12,000 / 20), essentially grab sampling at this sub-sampling stage, which would have eliminated the primary composite sampling objective with a 100% certainty. The mind boggles at the incompetence of the analytical laboratory head!

Figure 7. A show of futility. Shown here are genuine sampling and sub-sampling tools in a professional analytical laboratory. The issue was which tool is optimal for final analytical aliquot extraction: spoon vs spatula (the fork is supposed to be a mixing implement)? The mind again boggles at the incompetence revealed—grab sampling reigned supreme even at this ultimate, smallest scale.

It is fair to state, however, that this insight has not always been present in the gamut of scientific, technological and even occasionally in the sampling literature. A plethora of examples from the literature exist to justify the preceding harsh statement, but it suffices to present but a few spectacularly illustrative cases here. The matter presented above also occupies a central role in later columns under diverse headings, e.g. “Sampling Hall of Fame” and, perhaps more so, in “Sampling Hall of Shame”, all in good time.

The example in Figure 6 points forcefully to the issue that there must always be a unified sampling responsibility all the way “from-lot-to-aliquot”, of which more later.

Further reading

- P. Bedard, K.H. Esbensen and S.-J. Barnes, “Empirical approach for estimating reference material heterogeneity and sample minimum test portion mass for ‘nuggety’ precious metals (Au, Pd, Ir, Pt, Ru)”, Anal. Chem. 88, 3504–3511 (2016). doi: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03574

- K.H. Esbensen, “Materials properties: heterogeneity and appropriate sampling modes”, J. AOAC Int. 98, 269–274 (2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.5740/jaoacint.14-234

- K.H. Esbensen and C. Wagner, “Theory of sampling (TOS) versus measurement uncertainty (MU) – a call for integration”, Trends Anal. Chem. 57, 93–106 (2014).

- E. De Andrade, K.H. Esbensen, M.C. Fernandes and A.M. Lopes, “Amostragem representative para uma quantificao precisa de sementes geneticamente modificadas”, Ed by P.S. Coelha and P. Reis. Agrorrural – Contributos Cientificos, pp. 604–615 (2011). ISBN 978-972-27-2022-9

- L. Petersen, C. Dahl and K.H. Esbensen, “Representative mass reduction in sampling – a critical survey of techniques and hardware”, in Special Issue: 50 years of Pierre Gy’s Theory of Sampling. Proceedings: First World Conference on Sampling and Blending (WCSB1), Ed by K.H. Esbensen and P. Minkkinen, Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Sys. 74, 95–114 (2004).