Rhodri N. Owen, Steven L. Kelly and A. Gareth Brenton

Institute of Life Science, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, Wales, SA2 8PP, UK

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1255/sew.2021.a53

© 2021 The Author

Published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND licence

Mass spectrometry is a gold-standard analytical technique and is widely employed over a range of fields, from petrochemical, fine chemical through to medical applications. The types of instrumentation for sample separation, ionisation, mass analysis and detection that have evolved in analytical mass spectrometry are diverse; as the old colloquialism goes “it is a matter of horses for courses”. Our “GlowFlow” source design based on an Argon flowing glow-discharge may satisfy part of that landscape.

Introduction

One of the earliest, and possibly still the most widely used, ionisation sources is electron ionisation (EI).1 The ionisation process requires the analyte molecule to be in the gas-phase and introduced directly into a beam of electrons (typically 70 eV) in a high vacuum environment necessary for mass analysis. Gas-phase molecules interact with the fast electron beam, with around 1 in 105 molecules excited sufficiently to eject a valance electron forming a molecule ion species.2 EI persisted until the 1960s as the predominant ionisation method for small molecule work, such as petroleum mixture and non-polar chemical analysis.

Historically, there has been an imperative to address biological chemistry and, therefore, engage with polar chemical entities. Unfortunately, EI methodologies did not work at all well on biological molecules. They thermally degraded as scientists tried, largely unsuccessfully, to desorb these specimens into the gas phase. The decades to 1990 saw a plethora of methods to achieve viable biological mass spectrometry, with chemical ionisation,3 field desorption/ionisation,4 plasma desorption,5 thermospray,6 fast-atom bombardment (FAB)7 and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation8 invented. Electrospray ionisation (ESI)9,10 spectacularly achieved this goal, along with other methods such as atmospheric pressure chemical ionisation (APCI).11

Atmospheric pressure ionisation (API) was a key enabling technological step in modern mass spectrometry methods.12 API is now ubiquitous, both simplifying sample introduction by eliminating the “ion source vacuum” components and having led to a diversity of methods available to analysts.

Even with this profusion of new methods no universal ionisation method has emerged, especially one that straddles molecules from non-polar though to polar chemistries.

The success of ESI is that it is a “soft” method which means it produces little, if any, fragmentation and can be used to analyse thermally labile and less volatile molecules. In ESI, ions are generated from Brønsted acid–base chemical reactions,13 i.e. protonation for positive mode and deprotonation in negative mode, within those droplets generated by an electrosprayed jet of liquid. ESI works best at atmospheric pressure; in fact it was an important part of the enabling technology of ESI that nascent electrosprayed ions needed to be stabilised, otherwise they tended to be clustered with water molecules attached, or even fragment either unimolecularly or by collisional activation.14 Collisions with a background gas or an intentionally introduced gas stream was a neat solution to these problems, enabling both the declustering of molecule ions (e.g. clustered with numerous water molecules) and internally cooling them so as to reduce fragmentation. Of course, these advances were, in part, serendipitous taking many years of incremental R&D improvements to the original systems.9,10

ESI, however, does have some drawbacks, not all molecules can be protonated; for example, hydrocarbons where EI is often the preferred high-sensitivity method. The “Achilles Heel” of EI is that it operates at low pressure which requires complex and costly vacuum systems and sample inlets.

Therefore, an ionisation source that can bridge the techniques of EI and ESI would be highly advantageous, one that operates at atmospheric pressure and can ionise the broadest range of compounds from polar to non-polar. This was the motivation for us to start to investigate GlowFlow, since it showed promise to span a range of chemistries, although with yet to be characterised sensitivity and specificity.

Electrical plasmas, such as a helium atmospheric pressure glow discharge (APGD), could offer such a solution as they potentially have several pathways to form ions.15 The first step is the formation of the metastable helium (Hem) in the discharge, a highly energetic atom which has 19.8 eV of energy, enough to directly ionise most organic molecules and has a surprisingly long lifetime of up to 7870 s as it only de-excites through collision.16 In an intermediate step, the Hem atom ionises atmospheric gases, such as nitrogen or water vapour, or it can directly proceed to ionise sample molecules (M).

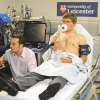

The aim of our study was to develop a compact APGD ionisation source that could be retrofitted to existing instrumentation and ionise compounds at atmospheric pressure which are less amenable to ESI. We named our implementation GlowFlow (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The GlowFlow ionisation source installed on a Waters Xevo G2-S universal source housing. The ionisation source is positioned on the right, with the electrical connection opposite the entrance to the mass spectrometer. A heated nebuliser used to desorb samples is shown at the top.

A selection of persistent organic pollutants and analogues was chosen for study as they can bioaccumulate in the environment and can have adverse health implications.

Methods

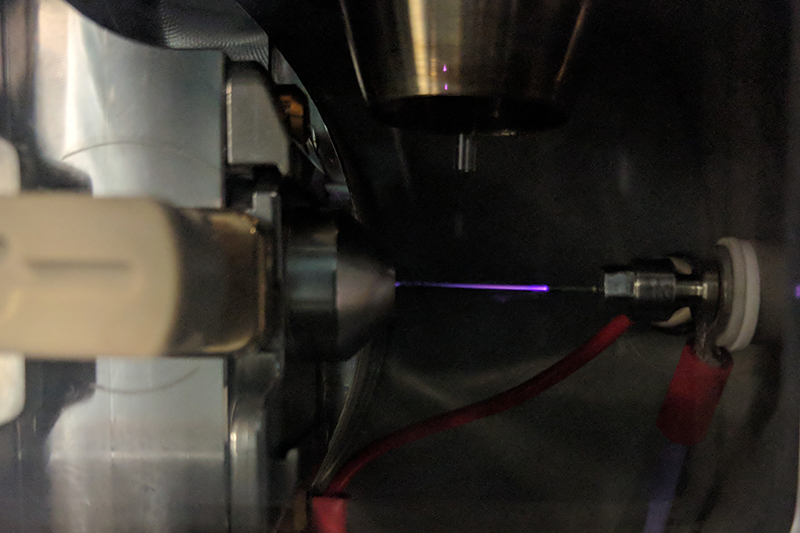

The design of helium glow-discharge sources is of two general types: either i) a glow discharge cell15 [see Figure 2(i)] that runs a discharge, typically at tens of watts of power, or ii) a simple nude design [see Figure 2(ii)] which generally operates at lower wattages, typically mW. Our design of the glow flow ionisation source used herein was made from an electrically insulating polyether ether ketone (PEEK), zero-dead volume union [Figure 2(ii)].17 Attached to one end was a stainless-steel tip which acted as the anode (ID = 0.5 mm) and was connected to the mass spectrometer’s internal power supply, operated in constant current mode (1–35 µA), typically set at 15 µA. To the other end of the ionisation source body was a helium gas line connected by a PEEK nut. A flow meter was used to regulate the gas flow rate (0.05–0.5 L min–1). High purity (99.999 %) helium was used for all experiments.

Figure 2. Illustrations of a cell design for a glow discharge and the “GlowFlow” method. i) A formal discharge cell design is commonly used15 in glow-discharge mass spectrometry with the cell often positioned off-axis at a critical angle to optimise sensitivity. The voltage on the anode is typically several hundred volts, sufficient to sustain the selected constant current required for the glow discharge. To initiate the glow, the voltage will often be raised significantly higher until the discharge ignites after which the voltage settles down again. ii) The GlowFlow design utilises a hollow PEEK union through which helium flows through and then over a sharpened tungsten electrode where the glow discharge forms and flows towards the ionisation region where the analyte flow occurs.

A Waters Xevo G2-S time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Wilmslow, Manchester, UK) was used for the analysis with the GlowFlow source fitted axially to the entrance for improved sensitivity. Standards of anthracene, naphthalene, pyrene, bisphenol A, bisphenol S, 1,4-dioxane, dibenzofuran and 2,8-dibromodibenzofuran (Tokyo Chemical Industry UK Ltd, The Oxford Science Park, Oxford, UK), and dodecane, tetradecane and octadecane (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, Dorset, UK) were prepared at concentrations of 1 µg mL–1. Methyl stearate (Alfa Aesar, Port of Heysham Industrial Park, Heysham, UK) was prepared at a concentration range from 5 pg µL–1 to 40 pg µL–1.

Results

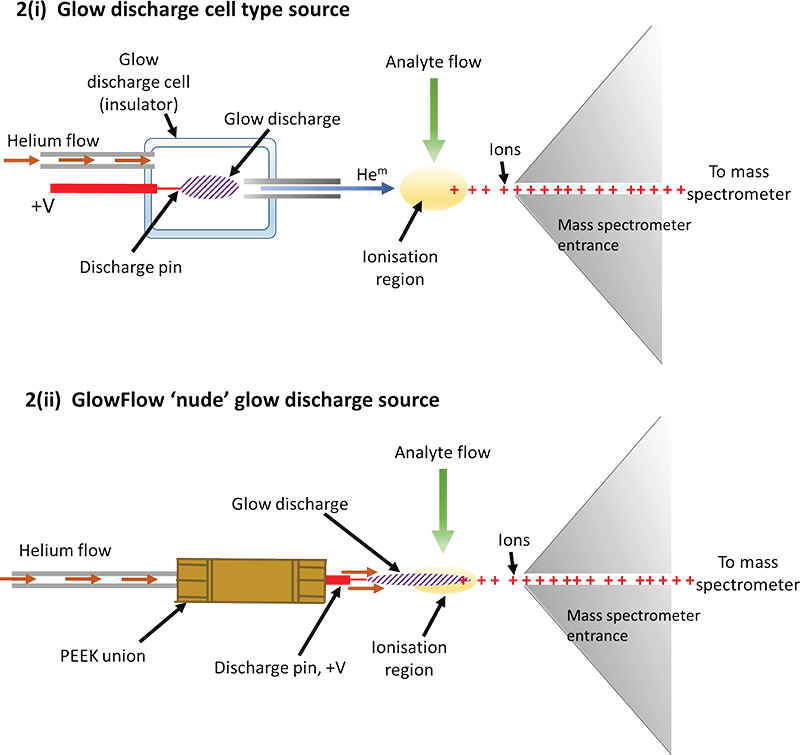

The GlowFlow ionisation source operates at gas flow rates of 0.05–0.5 L min–1 and can sustain a discharge at currents of 1–35 µA. To characterise the ionisation source’s capabilities, a separate experimental rig was made where the glow discharge was positioned perpendicularly to a metal plate which acted as a counter electrode and was connected to earth. A constant current of 10 µA was set on the instrument’s internal power supply and the GlowFlow source was moved away from the counter electrode in 5 mm steps from 5 mm to 40 mm and the readback current was recorded. Over relatively short inter-electrode gaps of 5–15 mm the current remained constant, but at the larger inter-electrode gaps >15 mm there was a noticeable reduction in the current (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Plot of recorded current as at varying electrode distances. The electrodes were moved in 5 mm steps from 5 mm to 40 mm. A comparison at different gas flow rates was also made. Relatively stable current is seen at 5–15 mm. At larger electrode distances (>15 mm) the current reduces due to a limit in the maximum voltage that can be delivered by the power supply. Panel A shows a long, purple plasma jet at the smaller electrode distances, while in panel B the glow is reduced in length reflecting the lower current.

The distinct purple glow of the discharge also shortened at inter-electrode gaps >15 mm leaving only a faint glow at the tip of the anode. To prevent the collapse of the glow discharge at larger distances, the actual current supplied must reduce as the voltage is reaching the power supply’s maximum operating threshold.

Persistent organic pollutants

Organic compounds that build up in the environment and tend to be classified as persistent organic pollutants. A range of these compounds and their analogues were prepared at concentrations of 1 µg µL–1, they ranged from non-polar hydrocarbons to polar compounds, such as bisphenol. A solids analysis probe was used to introduce samples, consisting of a metal body into which a glass capillary can be inserted. Samples are then syringed into the capillary before it is introduced into the source and a heated nitrogen gas nebuliser (programmable, ambient to 500 °C) desorbs/sublimates the sample for analysis using the GlowFlow ionisation source, with the mass spectrometer in full scan mode. A range of ions were observed in the mass spectrum and the most intense peaks were recorded (Table 1).

Table 1. List of significant ions observed in the mass spectra using GlowFlow ionisation source to analyse persistent organic chemicals and analogues.

Compound | Formula | Log P | Observed base peak | 2nd peak (%) | 3rd peak (%) |

1,4-Dioxane | C4H8O2 | –0.3 | 89 [M + H] |

|

|

Hexafluoro-2-propanol | C3H2F6O | 1.7 | 167 [M] |

|

|

Bisphenol S | C12H10O4S | 1.9 | 251 [M + H] |

|

|

Pentafluorobenzene | C6HF5 | 2.5 | 167 [M] |

|

|

Bisphenol A | C15H16O2 | 3.3 | 213 [M + H – O] | 229.12 (10 %) | 243.14 (5 %) |

Naphthalene | C10H8 | 3.3 | 129 [M + H] | 128 (95 %) | 145.08 (10 %) |

Dibenzofuran | C12H8O | 4.1 | 169 [M + H] | 168.08 (80 %) | 185.08 (5 %) |

Anthracene | C14H10 | 4.4 | 179 [M + H] | 178.10 (70 %) |

|

Pyrene | C16H10 | 4.9 | 203 [M + H] | 202.08 (80 %) | 219.08 (3 %) |

Dodecane | C12H26 | 6.1 | 147 [M – 23] | 185.19 (90 %) |

|

Tetradecane | C14H30 | 7.2 | 213 [M – H + O] | 211.17 (30 %) |

|

Octadecane | C18H38 | 9.3 | 269 [M – H + O] | 267.20 (40 %) |

|

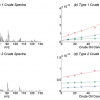

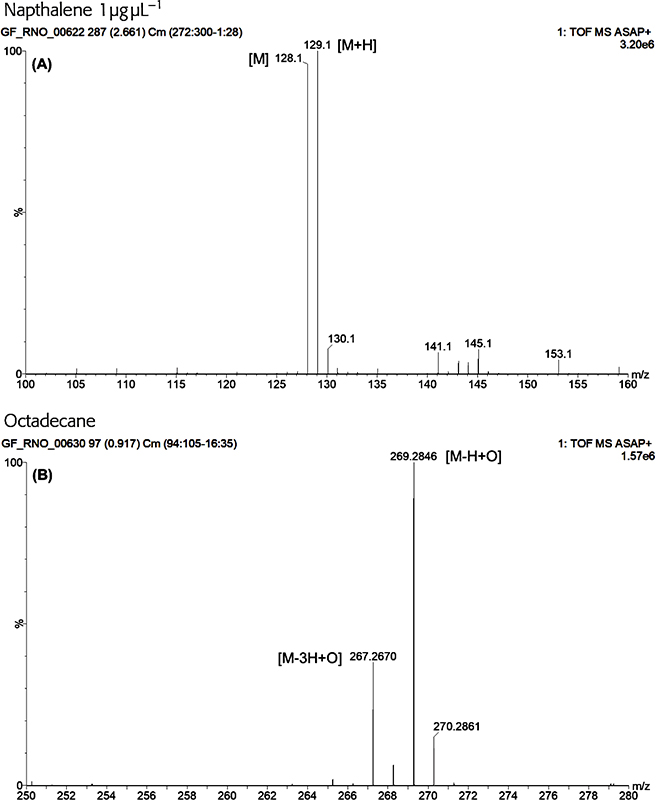

Typically, intense protonated molecules were measured for polar tending compounds and radical ions were measured for the more non-polar compounds. In some instances, the M+• and [M + H]+ ions were of equal intensity supporting the hypothesis that GlowFlow, like many other plasma ion sources, can access multiple ionisation pathways (Figure 4A). The base peak for hydrocarbons was M + 15, as seen in Figure 4B for octadecane, suggesting the hydrogen atom displacement by oxygen occurs readily for this class of compounds, following reactions in Scheme 1.18 Knowing this, sample chemistry could be used to establish the most favourable ionisation pathway and potentially suggests the potential for the ability to tune the source to selectively ionise.

Figure 4. A GlowFlow mass spectrum of naphthalene. Observed at m/z 128 is the M+• ion and at m/z 129 the M + H+ ion, demonstrating the multiple ionisation pathways available to the GlowFlow ionisation source (A). A GlowFlow mass spectrum of octadecane (B). Intense ions observed at m/z 269.2848 which correspond to C18H37O (δ = 0.3 mDa; the δ being the difference between the observed m/z and calculated exact mass of the monoisotopic peak).

Scheme 1. Hydrogen displacement by oxygen as observed in a GlowFlow mass spectrum of hydrocarbon molecules.

Figures-of-merit

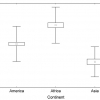

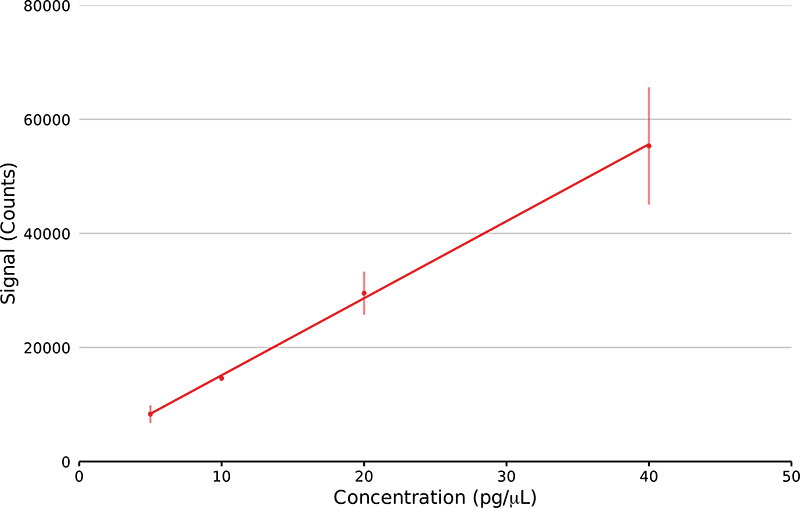

The sensitivity and reproducibility of the GlowFlow ionisation source was determined using methyl stearate. Serial dilutions were prepared at concentrations from 40 pg µL–1 to 5 pg µL–1. On the end of a glass capillary 1 µL of the solution was syringed and allowed to dry in the laboratory before being introduced by a solids analysis probe into the mass spectrometer. The peak area of the ion at m/z 299.29 was recorded and a calibration curve prepared, with five replicates at each concentration (Figure 5). The source lower limit-of-detection (LOD) was determined to be 111 fmol and had a coefficient of variation of 0.9991.

Figure 5. Linear regression plot of methyl stearate ion at m/z 299.29 at four concentrations from 5 pg µL–1 to 40 pg µL–1 (n = 5). The lower LOD was calculated.

Conclusion

Our ambition was to develop a high-sensitivity multimodal ionisation source that can analyse both atoms and molecules, polar to non-polar compounds with the broadest range of molecular masses. This study has shown the GlowFlow ionisation source can analyse a range of polar to non-polar compounds and is able to achieve low limits of detection (111 fmol for methyl stearate). Further work to interface this ionisation source with a range of chromatography is being actively undertaken, as well as to assess GlowFlow’s breadth of operation over a range of compounds. Our findings to date show that the source works for a wide range of molecules. For non-polar compounds, the ion species we generally observe are not normally the EI radical ion but various ion types, e.g. where a hydrogen atom is displaced by oxygen. For polar species, protonated molecules are commonly observed in GlowFlow, although at reduced sensitivities. Whereas, there appears to be great potential for GlowFlow in negative-ion mode as high sensitivity (recent data show <10 fmol) is often observed, with de-protonated species and occasionally dehydrated species typically observed. The technique readily interfaces to all types of chromatography and due to our compact design can be easily contained within many commercial source designs and be switched rapidly between active/inactive operation. Perhaps the simplicity of GlowFlow lends itself to be integrated with ESI and APCI setups, creating a near universal source assembly?

Competing interests

The GlowFlowTM ionisation source described in this article is marketed and sold by AberMS Ltd. Gareth Brenton is an Emeritus Professor in Swansea Medical School and a director of AberMS Ltd.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/R51312X/1) and from the ERDF/ Welsh Government funded BEACON project”.

References

- A.J. Dempster, “A new method of positive ray analysis”, Phys. Rev. 11(4), 316–325 (1918). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.11.316

- Note the terms and definitions we have used follow the revised definitions given by the IUPAC Committee in 2013, see K.K. Murray, R.K. Boyd, M.N. Eberlin, G.J. Langley, L. Liang and Y. Naito, “Definitions of terms relating to mass spectrometry (IUPAC Recommendations 2013)”, Pure Appl. Chem. 85(7), 1515–1609 (2013). http://doi.org/10.1351/PAC-REC-06-04-06

- M.S. Munson, and F.H. Field, “Chemical ionization mass spectrometry. I. General introduction”, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 88(12), 2621–2630 (1966). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00964a001

- H.D. Beckey, “Field desorption mass spectrometry: A technique for the study of thermally unstable substances of low volatility”, Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Phys. 2(6), 500–502 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7381(69)80047-1

- R. Macfarlane and D. Torgerson, “Californium-252 plasma desorption mass spectroscopy”, Science 191(4230), 920–925 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1251202

- C.R. Blakley, J.J. Carmody and M.L. Vestal, “Liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer for analysis of nonvolatile samples”, Anal. Chem. 52(11), 1636–1641 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1021/ac50061a025

- M. Barber, R.S. Bordoli, R.D. Sedgwick and A.N. Tyler, “Fast atom bombardment of solids as an ion source in mass spectrometry”, Nature 293(5830), 270–275 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1038/293270a0

- F. Hillenkamp, M. Karas, R.C. Beavis and B.T. Chait, “Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of biopolymers”, Anal. Chem. 63(24), 1193A–1203A (1991). https://doi.org/10.1021/ac00024a002

- J.B. Fenn, M. Mann, C.K. Meng, S.F. Wong and C.M. Whitehouse, “Electrospray ionization–principles and practice”, Mass Spectrom. Rev. 9(1), 37–70 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.1280090103

- M. Dole, L.L. Mack, R.L. Hines, R.C. Mobley, L.D. Ferguson and M.B. Alice, “Molecular beams of macroions”, J. Chem. Phys. 49(5), 2240–2249 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1670391

- D.I. Carroll, I. Dzidic, R.N. Stillwell, M.G. Horning and E.C. Horning, “Subpicogram detection system for gas phase analysis based upon atmospheric pressure ionization (API) mass spectrometry”, Anal. Chem. 46(6), 706–710 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60342a009

- G.A. Harris, A.S. Galhena and F.M. Fernandez,”Ambient sampling/ionization mass spectrometry: applications and current trends”, Anal. Chem. 83(12), 4508–4538 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1021/ac200918u

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Brønsted-Lowry Theory. Encyclopedia Britannica (21 April 2021). https://www.britannica.com/science/Bronsted-Lowry-theory [Accessed 2 November 2021]

- A.G. Brenton, R.P. Morgan and J.H. Beynon, “Unimolecular ion decomposition”, Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 30(1), 51–78 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pc.30.100179.000411

- J.T. Shelley and G.M. Hieftje, “Ambient mass spectrometry: approaching the chemical analysis of things as they are”, J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 26(11), 2153–2159 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1039/C1JA10158G

- S.S. Hodgman, R.G. Dall, L.J. Byron, K.G.H. Baldwin, S.J. Buckman and A.G. Truscott, “Metastable helium: A new determination of the longest atomic excited-state lifetime”, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103(5), 053002 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.053002

- R.N. Owen, S.L. Kelly and A.G. Brenton, “Towards a universal ion source: glow flow mass spectrometry”, Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 466, 116603 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2021.116603

- S.P. Badal, T.D. Ratcliff, Y. You, C.M. Breneman and J.T. Shelley, “Formation of pyrylium from aromatic systems with a Helium:Oxygen Flowing Atmospheric Pressure Afterglow (FAPA) plasma source”, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 28(6), 1013–1020 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-017-1625-z

Rhodri Owen

Mr Rhodri N. Owen is an analytical chemist and a final-year PhD candidate at the Institute of Life Sciences (ILS) at Swansea University Medical School. He holds a BSc in chemistry from Swansea University. He is also a Member of the Royal Society of Chemistry, the British Mass Spectrometry Society and the American Society of Mass Spectrometry. 0000-0002-3109-6653

0000-0002-3109-6653

[email protected]

Steven Kelly

Professor Steven L. Kelly is a geneticist and professor of biomedical sciences at the Institute of Life Sciences (ILS) at Swansea University Medical School. He is a Fellow of the Learned Society of Wales. He has also been awarded the George Schroepfer Medal from the American Oil Chemist’s Society for distinguished research on sterols. He holds a BSc in genetics, a PhD in yeast genetics and a DSc from Swansea University. He also worked at Sheffield and Aberystwyth Universities. 0000-0001-7991-5040

0000-0001-7991-5040

[email protected]

Gareth Brenton

Professor Gareth Brenton is an emeritus professor of mass spectrometry at Swansea University Medical School. He is also the first ever recipient of the International Mass Spectrometry Society Curt Brunnée Award, and the British Mass Spectrometry Society Medal. He holds a first class Hons BSc in physics and a PhD from Swansea University. He was elected as a Fellow of the Learned Society of Wales in 2012. 0000-0003-2600-2082

0000-0003-2600-2082

[email protected]