X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was developed in the 1960s and is accepted as a standard method in materials science. Researchers at Linköping University, Sweden, however, have shown that the method is often used erroneously.

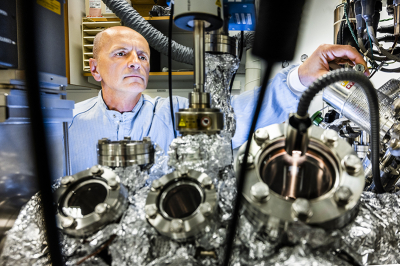

“It is, of course, an ideal in research that the methods used are critically examined, but it seems that a couple of generations of researchers have failed to take seriously early signals that the calibration method was deficient. This was the case also for a long time in our own research group. Now, however, we hope that XPS will be used with greater care”, says Grzegorz Greczynski, senior lecturer in the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology at Linköping University.

Grzegorz Greczynski and his colleague in the department, Professor Lars Hultman, have shown that XPS can give misleading analysis results due to an erroneous assumption during calibration. XPS is a standard method in materials science, and more than 12,000 scientific articles with results obtained by XPS are published each year. The technique was developed during the 1960s by Professor Kai Siegbahn at Uppsala University to become a useful and powerful method for chemical analysis, and the work led to him being awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1981.

“The pioneering work that led to the Nobel Prize is not in question here. When the technique was developed initially, the error was comparatively small, due to the low calibration precision of the spectrometers used at the time. However, as spectroscopy developed rapidly and spread to other scientific fields, the instruments have been improved to such a degree that the underlying error has grown into a significant obstacle to future development”, says Lars Hultman.

What the researchers have discovered is that the original method is being used wrongly, through an erroneous assumption used in the calibration process. When calibrating the experiment, the signal from elemental carbon accumulating on the sample surface is often used.

It turns out that the carbon-based compounds that are formed naturally by condensation onto most samples give rise to signals that depend on the surroundings and the substrate onto which they are attached, in other words, the sample itself. This means that a unique signal is not produced, and large errors arise when a more or less arbitrary value is used as reference to calibrate the measuring instrument.

Criticism of the method was raised as early as the 1970s and into the early 1980s. After that, however, knowledge about the error fell into oblivion. Lars Hultman suggests that several factors have interacted to allow the error to pass unnoticed for nearly 40 years. He believes that the dramatic increase in the number of journals that digital publishing has made possible is one such factor, while deficient reviewing procedures are another.

“Not only has a rapidly growing number of scientists failed to be critical, it seems that there is a form of carelessness among editors and reviewers for the scientific journals. This has led to the publishing of interpretations of data that are clearly in conflict with basic physics. You could call it a perfect storm. It’s likely that the same type of problem with deficient critical assessment of methods is present in several scientific disciplines, and in the long term this risks damaging research credibility”, says Lars Hultman.

Grzegorz Greczynski hopes that their discovery can not only continue to improve the XPS technique, but also contribute to a more critical approach within the research community.

“Our experiments show that the most popular calibration method leads to nonsense results and the use of it should therefore be terminated. There exist alternatives that can give more reliable calibration, but these are more demanding of the user and some need refinement. However, it is just as important to encourage people to be critical of established methods in lab discussions, in the development department, and in seminars”, Grzegorz Greczynski concludes.