A new imaging technology to grade tumour biopsies has been developed by a team of scientists led by the Department of Physics and the Department of Surgery and Cancer at Imperial College London. The method promises to significantly reduce the subjectivity and variability in grading the severity of cancers.

Nearly all cancers are still diagnosed by doctors taking a biopsy of the tumour, then slicing it thinly and staining it with haemotoxylin and eosin (H+E) and examining it under a microscope, from which they judge the severity of the disease by eye alone. Life-changing treatment decisions have to be based on this “grading” process, yet it is well known that different practitioners given the same slice will only agree on its grade about 70% of the time, resulting in an overtreatment problem.

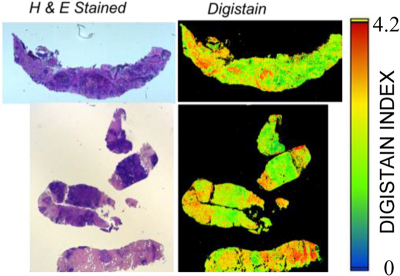

Imperial’s new “Digistain” technology addresses this problem by using mid-infrared imaging to map the chemical changes that signal the onset of cancer. In particular, they measure the “nuclear-to-cytoplasmic-ratio” (NCR): a recognised biomarker for a wide range of cancers.

In the work reported in Convergent Science Physical Oncology, the team carried out a double-blind clinical pilot trial using two adjacent slices taken from 75 breast cancer biopsies. The first slice was graded by clinicians as usual, using the standard H+E protocol. It was also used to identify the so-called “region of interest” (RoI), the part of the slice containing the tumour. The team then used the Digistain imager to get a DI value averaged over the corresponding RoI on the other, unstained slice, and ran a statistical analysis on the results.

The lead author Professor Chris Phillips, from the Department of Physics at Imperial, said: “Even with this modest number of samples, the correlation we saw between the DI score and the H+E grade would only happen by chance 1 time in 1400 trials. The strength of this correlation makes us extremely optimistic that Digistain will be able to eliminate subjectivity and variability in biopsy grading.”

The NCR factor that Digistain measures is known to be common to a wide range of cancers, as it occurs when the reproductive cell cycle gets disrupted in the tumour and cell nuclei get distorted with rogue DNA. It is likely that in the long run, Digistain could help with the diagnosis of all different types of cancer. At a practical level, the researchers say that the Digistain imaging technology can easily and cheaply be incorporated into existing hospital labs, and be used by their staff. Professor Philips added: “It’s easy to prove its worth by checking it with the thousands of existing biopsy specimens that are already held in hospital archives. Together these facts will smooth the path into the clinic, and it could be saving lives in only a couple of years.”