Studies have long shown that when faced with a problem that must be solved by cooperating with others, males and females approach the task differently. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered how those differences are reflected in brain activity. When the researchers asked people to cooperate with a partner and then tracked the brain activity of both participants, they found that males and females had different patterns of brain activity. The new findings, published in Scientific Reports, could offer some clues into how cooperative behaviour may have evolved differently between males and females, and could eventually help researchers develop new ways to enhance cooperative behaviour.

“It’s not that either males or females are better at cooperating or can’t cooperate with each other”, said the study’s senior author, Allan Reiss, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences and of radiology. “Rather, there’s just a difference in how they’re cooperating.”

Cooperation—between family members, friends, co-workers and even governments around the world—is viewed as a cornerstone of human society. But not everyone cooperates equally, as anyone who’s worked on a group project knows. And one factor shaping a person’s approach to cooperation is sex. Previous behavioural studies have found that women cooperate more when they’re being watched by other women; that men tend to cooperate better in large groups; and that while a pair of men might cooperate better than a pair of women, in a mixed-sex pair the woman tends to be more cooperative.

Theories have circulated about why this is, but the brain science behind them has been scarce. “A vast majority of what we know comes from very sterile, single-person studies done in an MRI machine”, said Joseph Baker, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford and a lead author of the study. The other lead author is research associate Ning Liu, PhD.

To work out how cooperation is reflected in the brains of men and women who are actively cooperating—rather than just thinking about cooperating while lying in a machine—the researchers turned to a technique called hyperscanning. Hyperscanning involves simultaneously recording the activity in two people’s brains while they interact. And to do this they used functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), in which probes are attached to a person’s head to record brain function, allowing them to sit upright and interact more naturally.

The 222 participants in the study were each assigned a partner. Pairs consisted of two males, two females or a male and a female. Then, while wearing the fNIRS probes, each person sat in front a computer, across the table from their partner. Partners could see each other, but were instructed not to talk. Instead, they were asked to press a button when a circle on the computer screen changed colour. The goal: to press the button simultaneously with their partner. After each try, the pair were told who had pressed the button sooner and how much sooner. They had 40 tries to get their timing as close as possible.

“We developed this test because it was simple, and you could easily record responses”, said Reiss. “You have to start somewhere.” It isn’t modelled after any particular real-world cooperative task, he said.

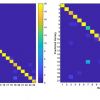

On average, male–male pairs performed better than female–female pairs at timing their button pushes more closely, the researchers found. However, the brain activity in both same-sex pairs was highly synchronised during the activity, meaning they had high levels of “interbrain coherence”.

“Within same-sex pairs, increased coherence was correlated with better performance on the cooperation task”, Baker said. “However, the location of coherence differed between male–male and female–female pairs.” This certainly isn’t probing cooperation in all its manifestations.

Surprisingly, though, male–female pairs did as well as male–male pairs at the cooperation task, even though they didn’t show coherence. Since the brains of males and females showed different patterns of activity during the exercise, more research might shed light on how sex-related differences in the brain inform cooperation strategy—at least when it comes to this particular type of cooperation.

“This study is pretty exploratory”, Baker said. “This certainly isn’t probing cooperation in all its manifestations.” There could be other cooperative tasks, for instance, in which female–female pairs beat males. And the researchers noted they hadn’t measured activity in all parts of the brain. “There are a lot of parts of the brain we didn’t assess”, Reiss said, pointing out that interbrain coherence may have been present in other regions of the brain that weren’t examined during the task.

As they continue to study what in the brain underlies cooperation, the scientists’ results could help explain how cooperation evolved in humans—and whether cooperation was selected for differently in males and females—as well as inform methods that use biofeedback to teach cooperation skills.

“There are people with disorders like autism who have problems with social cognition”, said Baker. “We’re absolutely hoping to learn enough information so that we might be able to design more effective therapies for them.”