A team from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) and supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) has used a new imaging technique using near infrared (NIR) radiation to measure how people break down dietary fat into products the cells of their bodies can use. The technique is a cost effective and convenient way to image the critical process of fat metabolism, and provides a way to test interventions aimed at reducing cardiovascular disease, diabetes and the increased risk of heart attack and stroke that can be caused by metabolic syndrome.

Doctors currently use a variety of less-than-ideal techniques to measure fat levels in patients. One common measure is the body mass index (BMI), a ratio of height to weight—but it cannot account for differences between muscle and fat. They can observe fat via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound—but neither method can determine activity levels within the tissue. Until now, it has not been easy to measure metabolically active fat, which consumes more oxygen and has more mitochondrial activity, and is associated with better health outcomes.

Now the UCI team has shown that both the composition and metabolism of fat tissue can be measured using diffuse optical spectroscopic imaging (DOSI). The technology uses NIR light to penetrate tissue and measure the concentrations of various molecules, like haemoglobin, water and lipids, such as fat.

“DOSI provides a new imaging method to measure the dynamics of fat”, said Behrouz Shabestari, director of the NIBIB programme in Optical Imaging and Spectroscopy. “It could provide a useful clinical tool for understanding metabolic disorders and providing new strategies for diagnostic monitoring of obesity and weight loss.”

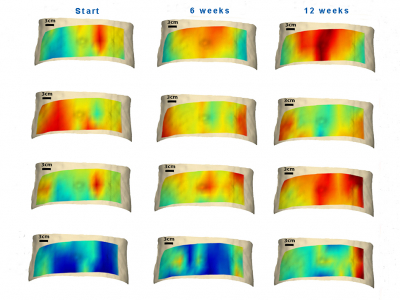

In their study in the International Journal of Obesity, the researchers enrolled 10 overweight people who followed a calorie-restricted diet for 12 weeks. At the beginning, middle and end of the 12 weeks, the researchers used DOSI to assess two measures: tissue scattering, which indicates change in cell volume due to the way particles within and between cells scatter light, and fluid absorption. Over the 12-week course of the dieting study, tissue scattering indicated that cellular particles shrank in size and increased in density, or how tightly they are compacted. The fat cells got smaller while the organelles within them, like the mitochondria, became more activated. The absorption signatures revealed an increase in the rates of metabolism, hydration, blood volume and delivery of blood to the tissue area.

“Essentially what we’re seeing is the metabolic activation of the lipid”, said Bruce Tromberg, director of the Beckman Laser Institute and Medical Clinic at UCI and senior author of the paper. “With the calorie-restricted diet, we’re seeing the lipid beginning to come alive. There’s enhanced perfusion, there’s oxygen consumption, and that’s an indication that the patients will undergo weight loss.”

DOSI is both inexpensive and easy to offer patients; it’s similar to performing an ultrasound. Because of this, individuals could be easily monitored over time to gauge the effects of different interventions.

“It could help people keep tabs on whether their diet and exercise is actually working and could be integrated into a series of measurements of fat and muscle”, said Tromberg, who hopes that one day it might be part of an index—along with things like BMI, blood pressure and cholesterol levels—to assess risk for metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. “We could characterise the biochemical composition of your fat cells and get some better insights.”