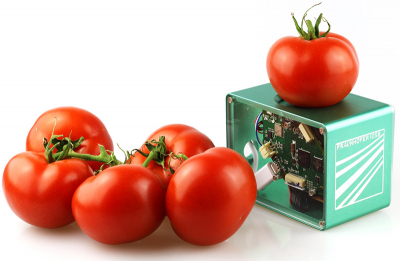

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Optronics, System Technologies and Image Exploitation IOSB, the Fraunhofer Institute for Process Engineering and Packaging IVV, the Deggendorf Institute of Technology and the Weihenstephan-Triesdorf University of Applied Sciences are developing a compact food scanner based on near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy to determine the ripeness and shelf life of produce.

“Foodstuffs are often counterfeited—for example, salmon trout is sold as salmon. Once suitably trained, our device can determine the authenticity of a product. It can also identify whether products such as olive oil have been adulterated”, says Dr Robin Gruna, project manager and scientist at Fraunhofer IOSB. However, the system can only evaluate the product quality of homogeneous foods. To enable the analysis of heterogeneous products such as pizza, the scientists are investigating high-spatial-resolution technologies such as hyperspectral imaging and fusion-based approaches using colour images and spectral sensors.

To be able to determine the quality of food based on the sensor data and the measured NIR spectra, and compute shelf-life predictions, the research teams are developing chemometric methods. “Through machine learning, we can increase the recognition potential. In our tests, we studied tomatoes and ground beef”, says Gruna. For example, we used statistical techniques to correlate the measured NIR spectra of ground beef with the rate of microbial spoilage and derived the remaining shelf life of the meat from the results. Extensive storage tests, whereby the research teams measured microbiological quality and other chemical parameters under various storage conditions, showed good correlation between the computed and actual total germ counts.

The scanner sends the measured data via Bluetooth to a database in the cloud for analysis. Then the test results are transmitted to an app that displays them to the user and shows how long the food item will remain fresh under different storage conditions, or indicates that its shelf life has already expired. In addition, the consumer is given tips on alternative ways of using food that is past its best-before date. A test phase is due to begin in supermarkets early in 2019, which will investigate how consumers respond to the device. More broadly, it is expected that the versatile technology will be used throughout the value chain, from raw material to end products.

The scanner has the potential to be used for many other applications where NIR spectroscopy can be applied. For example, it could be used to sort, separate and classify plastics, wood, textiles and minerals. “The range of potential applications is very wide; the device just needs to be trained accordingly,” says Gruna.