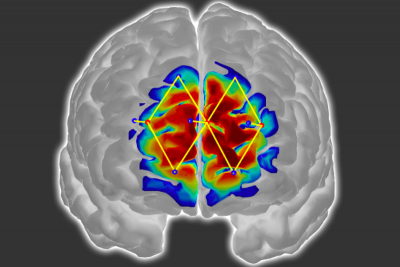

Researchers from MIT and elsewhere have developed a system that measures a patient’s pain level by analysing brain activity from a functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) device. The system could help doctors diagnose and treat pain in unconscious and non-communicative patients, which could reduce the risk of chronic pain that can occur after surgery.

Pain management is a surprisingly challenging, complex balancing act. Overtreating pain, for example, runs the risk of addicting patients to pain medication. Undertreating pain, on the other hand, may lead to long-term chronic pain and other complications. Today, doctors generally gauge pain levels according to their patients’ own reports of how they are feeling. But what about patients who cannot communicate how they are feeling effectively, or at all, such as children, elderly patients with dementia or those undergoing surgery?

The researchers use only a few fNIRS sensors on a patient’s forehead to measure activity in the prefrontal cortex, which plays a major role in pain processing. Using the measured brain signals, the researchers developed personalised machine-learning models to detect patterns of oxygenated haemoglobin levels associated with pain responses, which predicted whether a patient is experiencing pain with around 87 % accuracy.

“The way we measure pain hasn’t changed over the years,” says Daniel Lopez-Martinez, a PhD student in the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology. “If we don’t have metrics for how much pain someone experiences, treating pain and running clinical trials becomes challenging. The motivation is to quantify pain in an objective manner that doesn’t require the cooperation of the patient, such as when a patient is unconscious during surgery.”

Traditionally, surgery patients receive anaesthesia and medication based on their age, weight, previous diseases and other factors. If they do not move and their heart rate remains stable, they are considered fine. But the brain may still be processing pain signals while they are unconscious, which can lead to increased post-operative pain and long-term chronic pain. The researchers’ system could provide surgeons with real-time information about an unconscious patient’s pain levels, so they can adjust anaesthesia and medication dosages accordingly to stop those pain signals.