Thirty years ago, archaeologists excavated the tomb of an elite 40–50-year-old man from the Sicán culture of Peru, a society that predated the Incas. The man’s seated, upside-down skeleton was painted bright red, as was the gold mask covering his detached skull. Now, researchers have analysed the paint, finding that, in addition to a red pigment, it contains human blood and bird egg proteins.

The Sicán was a prominent culture that existed from the 9th to 14th centuries along the northern coast of modern Peru. During the Middle Sicán Period (about 900–1100 AD), metallurgists produced a dazzling array of gold objects, many of which were buried in tombs of the elite class. In the early 1990s, a team of archaeologists and conservators led by Izumi Shimada excavated a tomb where an elite man’s seated skeleton was painted red and placed upside down at the centre of the chamber. The skeletons of two young women were arranged nearby in birthing and midwifing poses, and two crouching children’s skeletons were placed at a higher level. Among the many gold artefacts found in the tomb was a red-painted gold mask, which covered the face of the man’s detached skull. At the time, scientists identified the red pigment in the paint as cinnabar, but Luciana de Costa Carvalho, James McCullagh and colleagues wondered what the Sicán people had used in the paint mix as a binding material, which had kept the paint layer attached to the metal surface of the mask for 1000 years.

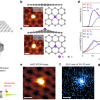

To find out, the researchers analysed a small sample of the mask’s red paint. FT-IR spectroscopy revealed that the sample contained proteins, so the team conducted a proteomic analysis using tandem mass spectrometry. They identified six proteins from human blood in the red paint, including serum albumin and immunoglobulin G. Other proteins, such as ovalbumin, came from egg whites. Because the proteins were highly degraded, the researchers couldn’t identify the exact species of bird’s egg used to make the paint, but a likely candidate is the Muscovy duck. The identification of human blood proteins supports the hypothesis that the arrangement of the skeletons was related to a desired “rebirth” of the deceased Sicán leader, with the blood-containing paint that coated the man’s skeleton and face mask potentially symbolising his “life force”, the researchers say.